This Antarctic Expedition Disaster Holds Key Leadership Lessons

Anyone can steer the ship but it takes a leader to chart the course.

An excerpt from the book: The 21 Irrefutable Laws of Leadership by John Maxwell

Law Number 4: The Law of Navigation

In 1911, two groups of explorers set off on an incredible mission. Though they used different strategies and routes, the leaders of the teams had the very same goal: To be the first in history to reach the South Pole.

Their stories are life and death illustrations of the Law of Navigation.

One group was led by Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen. Ironically, Amundsen had not originally intended to go to Antarctica. His desire was to be the first man to reach the North Pole. When he discovered that Robert Peary had beaten him there, Amundsen changed his goal and headed to the toward the other end of the earth. North or south, he knew his planning would pay off.

Before his team set off, Amundsen had painstakingly planned this trip. He studied the methods of the eskimos and other experienced arctic travelers and determined that their best course of action would be to transport all of their equipment and supplied by dog sled. When he assembled his team, he chose expert skiers and dog handlers. His strategy was simple. The dogs would do most of the work as the group travelled 15 to 20 miles in a six-hour period each day. This would afford the dogs and the men plenty of time for daily rest prior to the following day’s travel.

Amundsen’s forethought and attention to detail were incredible. He located and stocked supply depots all along the intended route. That way they would not have to carry every bit of their supplies the whole trip. He also equipped his people with the best gear possible. Amundsen had carefully every possible aspect of the journey thought it through and planned accordingly and it paid off. The worst problem they experienced on the trip was infected tooth that one man had to have extracted.

The other team of people was led by Robert Falcon Scott, a British naval officer who had previously done some exploring in the Antarctic area. Scott’s expedition was the antithesis of Amundsen’s. Instead of using dog sleds, Scott decided to use motorized sledges and ponies.

Their problems began when the motors on the sledges stopped working only five days into the trip. The ponies didn’t fare well either in those frigid temperatures. When they reached the foot of the Trans-Antarctic mountains, all of the poor animals had to be killed. As a result, the team members themselves ended up hauling the 200-pound sledges. Scott hadn’t given enough attention to the team’s other equipment either. Their clothes were so poorly designed that all the men developed frostbite. One team member required an hour every morning just to get his boots on to his swollen gangrenous feet. Everyone became snowblind because their inadequate goggles that Scott had supplied. On top of everything else, the team was always low on food and water that was also due to Scott’s poor planning.

The depots of supplies Scott established were inadequately stocked. Too far apart and often poorly marked which made them very difficult to find. Because they were continually low on fuel to melt snow, everyone became dehydrated. Making things even worse was Scott’s last-minute decision to take a fifth man even though they had prepared enough supplies for only four. After covering a grueling 800 miles in 10 weeks, Scott’s exhausted group finally arrived at the South Pole on January 17, 1912.

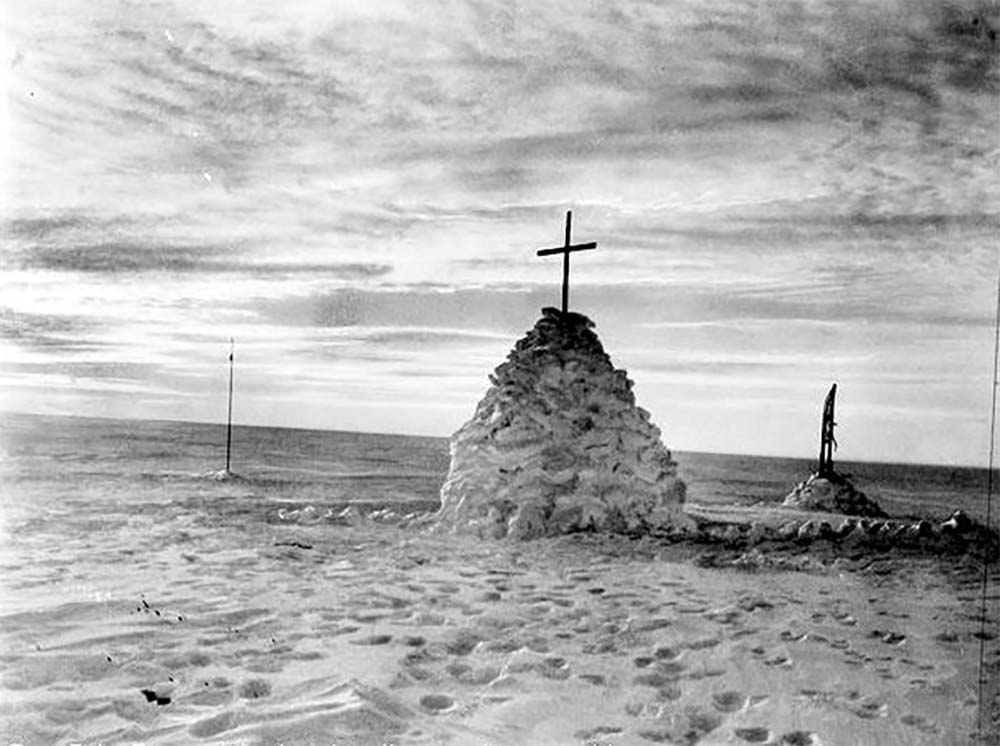

There they found the Norwegian flag flapping in the wind and the letter from Amundsen. The other well-led team had beaten to their goal by more than a month.

Scott’s expedition is a classic example of someone who could not navigate for his people.

But the trek back was even worse. Scott and his men were starving and suffering from scurvy yet Scott unable to navigate to the very end was oblivious to their plight. With time running out and the food supply desperately low, Scott insisted they collect 30 pounds of geological specimens to take back, more weight to be carried by the worn-out men.

The group’s progress became slower and slower. One member of the party sank into a stupor and died. Another, Lawrence Oates, a former army officer who had originally been brought along to care for the ponies had frostbite so severe that he had trouble doing anything. Because he believed that he was endangering the team’s survival, he purposely walked out into a blizzard to keep from hindering the group. Before he left the tent and headed into the storm, he said “I’m just going outside. I may be some time.”

Scott and his final two team members made only a little further north before giving up. The return trip had taken two months and they still were a 150 miles from their base camp.

There, they died.

We know their story only because they spent their hours updating their diaries. Some of Scott’s last words were these:

We shall die like gentlemen. I think this will show that the spirit of pluck and power to endure has not passed out of our race.

Scott had the courage, but not leadership. Because he was unable to live by the Law of Navigation, he and his companions died by it.